The comfort paradox - Get into the ZOUD

A very British problem

A very British problem

When was the last time you actively instigated an uncomfortable discussion? If you are reading this and experiencing an ‘inner squirm’ at the very idea of it, then it’s likely to be symptomatic of the very British problem of not addressing tricky situations head on.

We could well be doing ourselves a disservice in this deliberate swerve, given that our reticence and active avoidance of such discussions may cause us to feel disengaged, unproductive and, in certain situations, it could even prompt unethical and faulty thinking and actions.

Picture the scene; it’s 4.40pm and you are in your team meeting. Your boss announces amendments to a policy. You know that there are potential issues, and layered on this, you know the team knows that there are potential issues. People nod, a colleague comments that this was tried three years ago and created extra work. Your boss retorts that it is the new policy and as a team you all need to give it a go. There is an air of disquiet in the room and the tension is palpable.

Healthy conflict is important

If I told you that you would become more comfortable by allowing yourself to be uncomfortable, I imagine you would snort with derision. We are conditioned to believe that as soon as we experience any uncomfortable sensations, it’s a signal to retreat to a more familiar (metaphorical) place. Yet outside your comfort zone is where the real magic happens. I hope to convince you of this by the end of this blog.

When avoidance has cataclysmic results

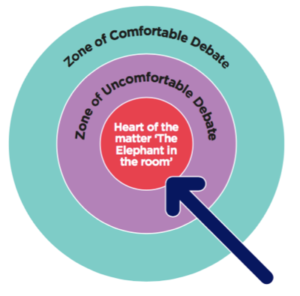

Professor Cliff Bowman of Cranfield School of Management noticed when researching teams that they only became truly productive if and when they enter a ‘Zone of Uncomfortable Discussion’ (ZOUD). The avoidance of uncomfortable discussion is an attempt to teeter around conflict, but at its worst, it’s a blatant denial of ‘what is’. You might ask yourself if the appalling catalogue of Jimmy Saville abuse cases would have surfaced earlier, or indeed the 2008 financial crash would have been of such seismic force had more people actively embraced the ZOUD. Two very contrasting and extreme examples, admittedly, but they demonstrate the point in its extreme. To quote The Big Short, “The truth is like poetry and most people ****ing hate poetry.”

Why are we so ZOUD-averse?

There are multiple reasons why we stand back when it comes to entering into uncomfortable discussions. The hierarchical nature of organisations is an obvious power dynamic to challenge this. Ego is a huge factor, as we often retain the status quo to preserve the egos of those around us, while also not wishing to be seen as a ‘troublemaker’. There may also be a historical narrative around this or a group mentality of ‘that’s not what we do around here’. It may simply look like it requires too much effort or there could be a strong ‘Parent – Child’ culture at work which dictates the way people interact.

How to embrace uncomfortable discussions

The ZOUD is a model that scaffolds difficult conversations and signals to all that the organisation is open to discussing core issues. According to Blakey & Day ‘Being in and maintaining dialogue with the ZOUD allows the heart of issues to be uncovered and resolved’.

Organisations entrenched in a fear-based culture, where speaking out about uncomfortable issues means risking humiliation, putting pressure on relationships or jeopardising career security, just perpetuate the myth. This creates a chasm between what people are talking about, and what is actually going on. We often stay within the parameters of comfortable discussion to show we’re ‘team players’ and to adhere to an unwritten code of conduct that doesn’t permit challenge or constructive criticism.

In truth, when we create a coaching culture that invites people to challenge assumptions in a healthy way, to reflect and question, it removes any notion of blame apportionment. It may feel uncomfortable when you start to engage in new ways of communicating, but the paradox is realised when you recognise that encouraging the team to have uncomfortable discussions actually deepens levels of trust and is ultimately liberating.